|

|

Google Books effort still enjoys academic support

Google Books has been trying for years to digitize and make available on-line millions of volumes of printed books from the world's libraries. Although the effort has been mired in endless litigation for years, it still enjoys substantial support from the academic community. Here is an article from the Stanford University Library newsletter, ReMix (April 2011):

Quo Vadis, Google Books?

In the wake of last month’s judicial rejection of the proposed settlement of litigation between Google Books and various publishers and authors, there are only two firm facts that can be confidently stated about what’s next: first, nobody, with the possible exception of the litigants, knows anything; and second, the litigants aren’t talking. Thus we have the conditions for rampant public speculation, and many have risen to this temptation. I shall not.

Instead, I remind readers that the scanning of millions of books by the Google Books project has never abated, either at Stanford or among the many other participating libraries. Every weekday, a truckload of books goes to Google and a like number come back from them, in a smoothly choreographed process that assures both safekeeping and tracking of the books. The total to date is in the vicinity of two million volumes, and we anticipate continuing this process for years to come. We do not know how or even if any given book will be used by Google, but we are certain of the utility to Stanford in having our holdings preserved and being made searchable through digitization. We are hopeful of additional beneficial outcomes for Stanford.

The key word in Stanford’s public reaction to the demise of the proposed settlement was “disappointment.” That, almost five years after the class-action suits were initiated against the project, there is no resolution whatever is certainly disappointing; any decision might seem preferable to none. That a startling vision of public access to a vast amount of text as articulated in the proposed settlement has been occluded is another disappointment. That the “orphan works” and other copyright issues remain in limbo is a lesser disappointment, if only because efforts are underway to address them by legislative rather than judicial means. However, the key word I wish you to take away is “persistence.” We persist in scanning books through Google (as well as in our own labs). We persist in developing techniques to help scholars use digitized texts. We may be confident that the litigants will persist in seeking some eventual resolution to the court case. We persist in hoping that the discordance between copyright law and the realities of the digital age will be harmonized, at least with regard to printed literatures, before the century is much further along. We persist in fulfilling a vision and mission that depend on both digital and artefactual means of providing and preserving information.

Looking forward, but unprophetically,

Andrew Herkovic

Short Resource List for Minoan Crete

One of the best introductions to the rediscovery of Minoan civilization is Alexandre Farnoux's Knossos: Searching for the Legendary Palace of King Minos (1996, 159pp), part of the excellent Discoveries series (i.e., concise, lavishly illustrated, with selected historical documents). The Minotaur's Island is an informative, if somewhat melodramatic, video documentary (2008, 98 minutes, available through Netflix or Amazon) featuring historian Bettany Hughes summarizing what we know about Minoan Crete today. Cathy Gere's Knossos & the Prophets of Modernism (2009, 234pp. also in Kindle format) details how the rediscovery and interpretation of Minoan culture was heavily influenced by a war-ravaged Europe's eagerness to find and embrace a more benign and peaceful cultural heritage. For those who enjoy historical fiction, Mary Renault's classic The King Must Die (originally 1958, but numerous recent editions plus audiobook format) retells the legend of Theseus' encounter with the Minoans, against the backdrop of a cataclysmic volcanic eruption. Compiled by Chuck Sieloff

Short Resource List for Toledo: Multicultural Challenges of Medieval Spain

If you would like to do some additional reading or research related to the Humanities West program on Toledo (Feb. 4 and 5, 2011), the following short list of recommended resources is a good starting point.

Chris Lowney’s A Vanished World: Muslims, Christians, and Jews in Medieval Spain (2006, 320pp) focuses on the messy reality of a multicultural society in which the pragmatic need to coexist goes hand-in-hand with factionalism, political fragmentation, and ever-shifting alliances that often crossed cultural boundaries. Maria Rosa Menocal gives a somewhat more idealized and romanticized view of “convivencia” in The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain (2003, 352pp, available in Kindle format). Menocal also co-authored (with Jerrilynn D. Dodds and Abigail Krasner Balbale) an award-winning study of cross-cultural influences in Castillian art, architecture, and literature: The Arts of Intimacy: Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Making of Castillian Culture (2009, 416pp). The book, which focuses on Toledo, is lavishly illustrated and includes a 64-page bibliographic essay and a detailed chronology. Teofilo Ruiz, a featured speaker at the program, has created a Teaching Company video course, The Other 1492: Ferdinand, Isabella, and the Making of an Empire (12 half-hour lectures) which provides excellent historical background and context, although its emphasis is on the transition from medieval Iberia to modern Spain, rather than on the long period of Muslim/Christian/Jewish coexistence.

Early Italian musical instruments

The Viola da Gamba

The viola da gamba (also called the "viol" or "gamba") is not a fretted cello! [A] cello has 4 strings and a viol usually has 6, like a guitar, or 7. In addition, the viol's frets . . . are . . . made of gut tied onto the neck, like those of a lute, and are therefore movable. Viols are bowed, like cellos, but the bow is held . . . underhand, like a pencil or chopsticks. . . . The smallest, highest-sounding member is a treble viol, equivalent to the violin. Next larger and deeper in tone is the tenor viol, approximately equivalent to the viola. Even larger and deeper-sounding is the bass viol, equivalent to the cello. The largest, deepest size, the double bass, is the only viol played in orchestras today.

Viols have a long history. They were perhaps most popular in the 15th to 18th centuries, from about the time of Henry VIII of England, who played them, to that of Louis XIV of France (the Sun King). Shakespeare mentions them in several plays, including Twelfth Night. The sound of the viol is sweet and shimmering, quieter than that of violins, violas, or cellos. [ source]

Come and see David Morris make music on the viola da gamba on October 22 at the Herbst Theatre.

The Bassetto Simone Cimapane

The Bassetto Simone Cimapane is a cello of big proportion, almost a "bassetto" or a "basso di violino", made in Rome by Simone Cimapane in 1685. Simone Cimapane was active in Rome as a maker of string instruments and as a musician during the second half of the seventeenth century and he played with Arcangelo Corelli. His name appears in the "Societá del Centesimo" that was created by the members of "Congregazione di Santa Cecilia" in Rome in 1688. He is also mentioned in the lists of musicians employed by Cardinal Pamphili, together with others musicians under Corelli. Most likely Simone Cimapane was father of Bartolomeo, a double bass player active in Rome during the time of Corelli. At least two others members of this family were active musicians: one a violin player and one a singer. This instrument has original measure and is considered an Unicum, an instrument of historical importance because it was played in the Orchestra of Arcangelo Corelli. For its features and historical relevance, it belongs in the Italian musical heritage. [Text provided by Alessandro Palmeri]

Additional images of the Bassetto Cimapane during restoration may be found here.

Come and see Alessandro Palmeri make music on the Bassetto Cimapane on October 23 at the Herbst Theatre and October 24 at SF Conservatory.

Short list of recommended resources for Venice: Queen of the Adriatic

Elizabeth Horodowich has written a short and very readable summary, A Brief History of Venice: A New History of the City and Its People (2009, pb, 230pp), which includes brief references to the physical remains from each period that may still be seen today when visiting the city. Somewhat denser is William H. McNeill’s Venice: The Hinge of Europe, 1081-1797 (originally published in 1974, reissued in 2009, pb, 323pp), which focuses more attention on Venice’s relations with the Byzantine and Ottoman Empires and the emerging European powers. If art is your primary focus, Patricia Fortini Brown’s Art and Life in Renaissance Venice (2005, pb, 176pp) provides historical and social context along with excellent illustrations. Jan Morris originally wrote her impressionistic portrait of Venice fifty years ago, but has revised it several times for later editions. It is currently available as Venice in Kindle (2008, 336pp) and Audiobook (2010, 5:16 hours) formats, and in book form as The World of Venice (1995, pb, 320pp). Our featured speaker for the Friday evening program (Oct. 22), Joanne Ferraro, provides an unusual perspective on Venice’s social history and the role of women in Marriage Wars in Late Renaissance Venice (2001, 240pp, also available in Kindle), based on her examination of court records of marital disputes.

Remember, if you are ordering any of these books (or anything else) from Amazon, you can help Humanities West by ordering through our Amazon Affiliates link. We get 4-6% of your purchase price, at no additional cost to you. Just one additional click.

Historical fiction set in Venice

Humanities West programs offer a kind of cross-disciplinary immersion in some particularly interesting historical setting. Another way to add a dimension to that immersive experience is through historical fiction that shares a similar historical and cultural setting. Although you may have to sift through some schlocky (and wildly inaccurate) works that are simply looking for an exotic background, good historical fiction is meticulously researched and goes to great lengths to recreate the atmosphere, the look-and-feel, and even the psychological mindset of its period. A fictionalized plot, set against a backdrop that often includes real historical places, events and personalities, can bring a distant period to life in a way that few works of straight history are able to do.

It should come as no surprise that Venice, the focal point of our Oct. 22-23 program, has figured prominently in many works of historical fiction. But where to start? It turns out that there is an excellent web site called Historical Tapestry. "We are a group of readers who love to read Historical Fiction set in all eras. Historical Tapestry is exclusively devoted to Historical Fiction."

In response to a request for information about works set in Venice, the folks at Historical Tapestry have compiled a list organized by historical period, with the bulk of the works set in the 15th and 16th centuries. While I can't claim to have read all these books, based on a perusal of Amazon summaries and reviews, it looks like Elle Newmark's The Book of Unholy Mischief or Thomas Quinn's The Lion of St. Mark might be good places to start. The Newmark book is also available in Kindle and Audiobook formats.

Feel free to add your own recommendations or critiques if you are familiar with these or any other works of historical fiction set in Venice.

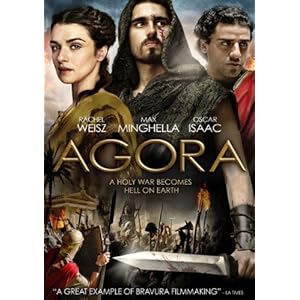

Agora: a film about Alexandria, astronomy, and a woman of science

Agora is not your typical summer blockbuster. You may even have trouble finding a theater where it is currently playing. But the movie is centered on some themes that will undoubtedly resonate with fans of Humanities West, especially those who attended last season's programs about astronomy (in October 2009) and Alexandria (in February 2010).

This is the story of Hypatia, the brilliant female philosoper, mathematician, and astronomer, who lived and taught in Alexandria at the end of the fourth century and beginning of the fifth century, when Alexandria was being torn apart by factional strife between the Hellenistic pagans, the Jews, and the rapidly rising Christians. Hypatia, who has been called "the last of the Hellenes", had a devoted following that included members of all three cultural strands, but her dedication to a life of reason and empirical skepticism brought her increasingly into conflict with the faith-based fanaticism of the Christians, who eventually destroyed the multi-cultural cosmopolitanism that had made Alexandria the cultural and scholarly center of Mediterranean civilization for centuries. The brutal public murder of Hypatia by an organized mob of Christian militants in 415 AD may also be seen as the symbolic end of the Hellenistic era that our program celebrated. (The image below is from Raphael's School of Athens.)

The film's depiction of factional strife in Alexandria, although sometimes uncomfortably graphic, seems to follow historical accounts rather accurately. Its re-creation of ancient Alexandria and of everyday life in the streets, as well as in the scholarly precincts of the Library, are impressive and convincing. The film also depicts Hypatia's intellectual struggle to challenge the assumptions of the dominant geocentric model of Ptolemaic astronomy, and replace it with a simpler, more elegant heliocentric model, a theory that would take more than a thousand years (and the invention of the telescope) to gain widespread acceptance. This account is credible (based on Hypatia's scholarly accomplishments and on the existence of competing heliocentric theories in the Greek tradition), but is also highly speculative, since little direct evidence of her work survived.

If you enjoy historical dramatizations, this film is worth seeing. If you are unable to find it in a theater, the DVD can be pre-ordered through Netflix or Amazon, although it will apparently not be available until later this Fall.

|

|